Within the world of poetry, it is axiomatic that poems must exist on their own, their aboutness articulable inside the four corners of the page on which they exist. And this is an expectation with which I struggle most of the time, for I am a person who googles, wikis, and IMDBs my way through nearly every crumb of consumable content, crafting in my head quilted critiques of a thing as though preparing a dissertation on the matter. I feel about footnotes and endnotes the way most people who wear dresses feel about pockets. I eagerly descend rabbit holes, run down leads, and embark upon side quests, in hopes of conspiratorially connecting dots appearing precarious to others.

I suspect this desperate dot-connecting is an adoptee thing, the outcome of being raised without the mirrors of biology, without the attachment to culture and lineage. Even in middle age, I am still trying to attach my existence to almost anything; still searching for an explanation as to how I got here. And by “here,” I don’t mean my apartment on the Upper West Side in June of 2025 when I am writing this. I mean here on Earth in August of 1977.

This is what it is to be an adoptee who will never know her origin story.

The dozen pieces that make up Performance Anxiety, in nearly every case, originated as pieces of other works. It was only during various manuscript revision processes that I realized I had a cohort, this poetic dozen pieces, with something in common beyond their autobiographical roots—all the pieces deal in aspects of performance. Which means also, perhaps, the speaker is performing for the reader and, since I hope that you will read the poems, it means the speaker will, at some future date, perform for you.

If you have found yourself dizzy with that last explanation, congratulations, you now understand a little of what it’s like to live in the brain of an adopted person.

All that said another way: You, Reader, play a part in this performance.

When I have had occasion to log line the collection, I have said something about it standing atop the line between fact and fiction, actor and audience, life and livelihood. As an autobiographical collection, these dichotomies (false as they are), are meant literally as it pertains to me, an infant adopted to cure a white couple’s infertility, a teenage girl-child in the era of heroin chic models and Music Television, a very occasional theater kid whose acting career both rose and peaked in the role of Shelby in a small, undergraduate production of Steel Magnolias.

For a time a few years ago, I picked up background extra work on local television and film sets around the city. I mourned at Logan Roy’s Succession funeral; marched the hallways, a quant at Mike Prince’s Axe Cap in Billions; stood in for a Real Housewife of New York; and played reporter in a scene for the 2024 HBO Max limited series The Penguin, based on the DC Comics character of the same name. Part of the Batman franchise and set in the fictional Gotham City, I found myself on the grounds of a Long Island mega-mansion, confronted over numerous, repetitive takes, by violence as fantastical entertainment, far from real violence repeated in the real world somewhere off-set.

In the scene’s final cut I am clearly visible, if only for a few seconds, demanding information from an actor in a police officer’s uniform, looking quite comfortable, albeit angry, in the frames, dramaturgical inspiration perhaps coming from my own prior life. I was once married to a police officer.

I was not a happy wife, a condition rooted in attachment wounds I had no name for until much later, but most of the time, especially outside the house, I could play one. And I could fantasize, as I did, of the nights I could not and would not have with a friend’s boyfriend’s brother who visited one New Year’s Eve, and who was, like my husband, also a police officer. My husband and I would later divorce, and this second, fantasy fodder of an officer would be fired by his department for dragging a young Black girl across a classroom and throwing her against a wall, a fact I would learn watching the video of his brutality replay on cable news.

Watching him on television, I felt much closer to the danger than I really was. Or maybe, it is more accurate to say, only after the danger had passed me by in favor of another, darker girl, did I realize how close to it I had been. Like sitting on your white parents’ couch watching a white man on television get dragged from a truck and beaten by four Black ones.

I have transitioned now and I am speaking of a very specific cultural moment that younger people, my kids’ age, maybe, if I had kids, do not recognize by vague reference but that I am of a generation who will never forget, so let me tell that last anecdote again but from earlier on in the timeline so it is more easily recalled by you, sitting on your own couch, perhaps with your own parents or siblings on March 3, 1991, when a Black motorist named Rodney King was struck with a baton more than 30 times, and kicked in the neck at least six times, by four white LAPD officers, and the whole thing was captured on VHS in grainy black and white. And later on, when the officers were acquitted, Los Angelinos, especially the Black and brown ones, got angry. Violence ensued and a white man named Reginald Denny was dragged from his truck and beaten by four Black men at the intersection of Normandie and Florence.

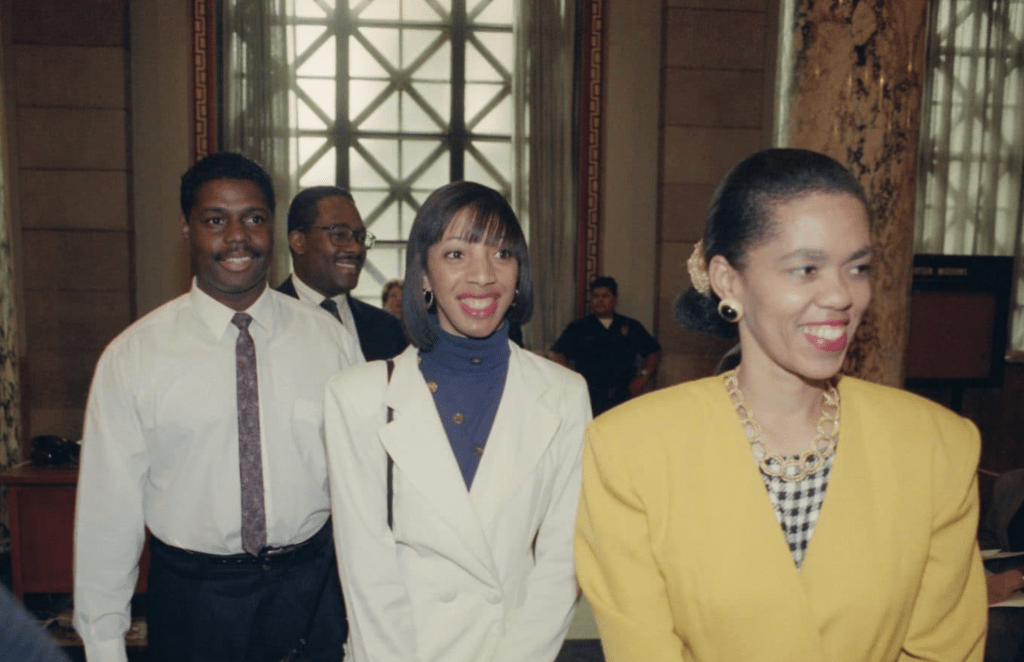

Four other Black people watching on television, left the safety of their homes and rescued Denny.

I imagine those four people, Bobby Green, Jr., Titus Murphy, Lei Yuille, and Terri Barnett, none of whom knew Denny or had any connection to him, believed themselves pressed up against the line of audience and co-conspirator when no one else did, and they acted accordingly, on the right side of humanity, and of history.

Police patrol six of the twelve pieces in this collection, which I’m afraid makes me a co-conspirator in a kind of violence that, even when it does not involve law enforcement, is abundant in this collection. This is an interesting observation given I was raised in a home free from physical violence, and the state of my youth is routinely ranked among the safest in the country. It is also routinely ranked among the whitest in the country, and so perhaps it is my subconscious that does not differentiate between fear of physical harm, and something vague, unnamable and unnerving, like being dripped on by an overhead air conditioner.

It was just a few years after the uprising in Los Angeles when I moved to New York for the first time, then I left, then returned, then left and returned again during the pandemic, at a time when everyone was either leaving or had left, and there were complaints, so many complaints about crime and the crime rate and criminals all over the city and especially in the subway, which I was warned not to ride after dark, an admonition in the Black mayor’s city I never heard when I lived here under white mayors. A young woman was pushed onto the tracks and, as I look for the details while writing several years later, I can’t figure out which of the subway push victims I think I’m remembering, but it was before Jordan Neely.

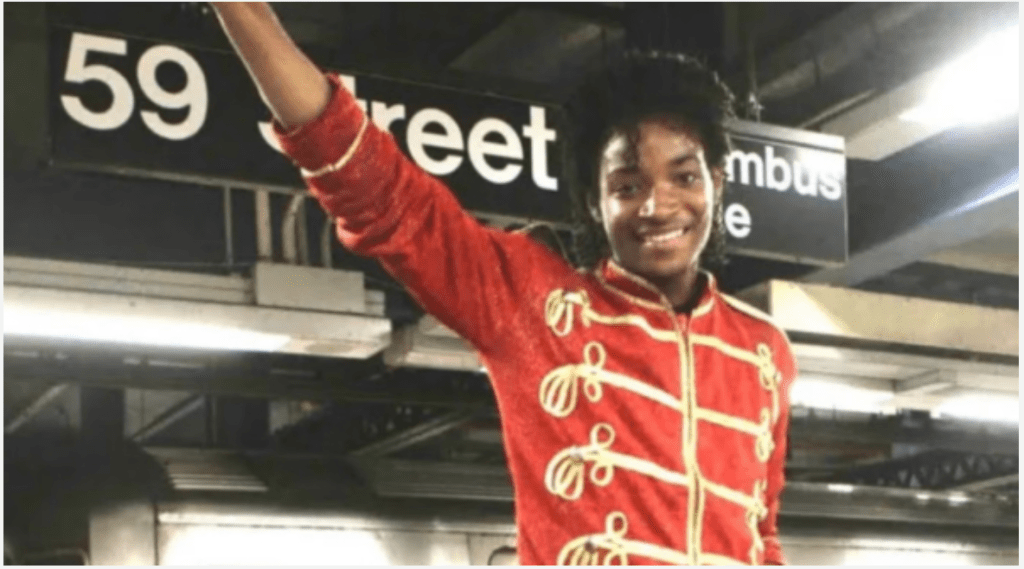

Jordan Neely, a Michael Jackson impersonator, was choked to death on the F train on May 1, 2023. His white killer, Daniel Penny, was found not guilty. I could add here Penny’s defense—that Jordan Neely, mentally ill and unhoused, was scaring the other passengers. But that’s not the part I think about when I ride the train after dark, typically alone and hyper-alert to the sight and the smells of those around me. The part I think about is that Jordan Neely was murdered at 2:30 on a Monday afternoon in a train car full of people who watched Penny choke him for six whole minutes despite clear indications Jordan Neely was dying, an audience, having paid for their ticket, content to remain in their seats for the duration of the show.

Six months following the murder, Percival Everett’s book, Erasure, was adapted for the screen and released as American Fiction, a satire about racial authenticity, meta-fiction, literary parody, and media culture. That same month I participated in a poetry marathon, 30 poems in 30 days, with Tupelo Press. I called my project, A Hole in the News the Size of Poetry, my own satirical wink to the former New York Times Poetry Editor who’d recently resigned in protest against her paper’s coverage of the war in Gaza that began that fall writing, “If this resignation leaves a hole in the news the size of poetry, then that is the true shape of the present.” Each day I chose one article from the New York Times and, using only the words contained within that article, a limited word bank if you will, crafted a poem, in this way, putting my poetry in direct conversation with the day’s news, as it was happening. Three of the poems in the collection originated as part of that project.

The articles from which the poems originated are: Pamela Paul, “The Truth in American Fiction,” New York Times (December 14, 2023); Jessica Bennett, “The Joy of Communal Girlhood; the Anguish of Teen Girls,” New York Times (December 22, 2023); and The Styles Desk, “Styles’s 71 Most Stylish ‘People’ of 2023: OK, some weren’t people, but they all made us talk: about what we wear, how we live and how we express ourselves,” New York Times (December 6, 2023).

Of course, one cannot talk about media or performance culture without talking about music, and it exists both in the background and in the foreground of the collection. Bruce Springsteen and Harry Stiles, who sold out MSG some two decades apart, mark the passage of time. The silence of Tori Amos, the nostalgia of Broadway’s Winter Garden Theater, Junior Vasquez’s Palladium, an imaginary Isaac Hayes/Ace Frehley mashup, even the instantly recognizable, two-beat DUH-DUH of Law & Order (more police) all soundtrack the collection, as does Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl,” with its cringeworthy accompanying ripoff of a 1985 Toni Basil video.

Titling a poem after Stefani and her song (Appreciation? Appropriation? Satire? Parody?), a shorthand for several of the very questions posed in the poetry.

Ultimately, Reader, it is up to you to determine what in the collection reads as authentic, what reads as performance, and what reads as what might be called authentic performance, the kind for which bodies are sacrificed, awards given.

Enjoy the show.